Winds across Illinois are beginning to still. A new study led by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign researchers has found that average wind speeds across the state have declined over the past three decades—and that the prevailing wind direction is slowly shifting southward. The findings, published in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, have significant implications for everything from wind energy production to weather forecasting and climate modeling.

“All of this started because we wanted to look at observational data versus models to see how well the models reproduced winds,” said Allison Wallin, a graduate student in the Department of Earth Science and Environmental Change at Illinois and lead author of the study Recent Wind Stilling and Variability in Illinois. “Illinois is fifth in the country in terms of wind power capacity. They use these models for wind power projections, so we wanted to see if they are accurate and what’s going on with wind in the state.”

Comparing models and real-world observations

To accomplish this, Wallin and her collaborators—Jessica Conroy, professor of earth science and environmental change, Trent Ford, Illinois State Climatologist, Jennie Atkins, Water and Atmospheric Resources Monitoring Program manager at the Illinois State Water Survey, and Christina Karamperidou professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa—compared three decades of observational weather station data to three major reanalysis datasets.

Reanalysis datasets are models that blend weather observations with numerical simulations to create a comprehensive record of atmospheric conditions. They are widely used to validate climate models and project future trends, including wind energy potential. But the models and the observations didn’t line up.

“There are huge ranges in what the climate models think wind will do in the future,” Wallin explained. We’re trying to figure out if the reanalysis data is accurate, so we wanted to look at station data and directly compare it to the reanalysis data to see if the models are accurate.”

Wind speeds are slowing and shifting southerly

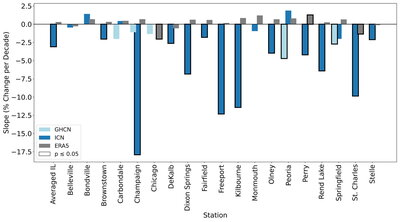

The team found it striking that wind speeds are slowing down across most of the state. While the weather station data show clear decreases in wind speed, most of the reanalysis datasets show little to no change, and in some cases, even slight increases.

“Some stations had decreases per decade of 5 percent, while others, like the one in Champaign, were 15 percent,” Wallin noted. “It was variable across the state, but most stations had a decrease over the 30 years. That would have huge implications for wind power generation across the state. Even small changes in wind speed at the surface would result in significant reductions in wind power production.”

At the same time, the researchers identified something not shown in the reanalysis data: a subtle but important shift in wind direction. At several Illinois sites, the data show winds are increasingly coming from the south, suggesting a growing influence of air masses from the Gulf of Mexico.

“Other studies have found that when there is more transport from the Gulf of Mexico, there has been more humidity, flooding, tornadoes, hail, and extreme weather events in the Midwest,” Wallin explained. That shift matters because it points to broader changes in the region’s climate, and reanalysis models to capture them accurately.

“If the wind power companies are using these reanalysis datasets to look at future wind trends, most data shows no change over the past 30 years,” Wallin said. “So they may think the winds will remain stable, whereas the weather station data shows a decrease. Which would mean they have less power generation than they were expecting.”

Local data with global implications

The project was made possible by the Illinois Climate Network, a system of long-term monitoring stations across the state that track weather and soil conditions operated by the Illinois State Water Survey. This paper analyzed data from 23 weather stations across Illinois collected between 1992 and 2021, 18 of which were part of ICN.

The network’s historical record proved essential to uncovering long-term changes. “It’s crucial,” Wallin said. “You typically look at climatologies, which are defined by 30-year periods, when you look at long-term weather and climate. So having 30 years of data is enormous.”

The findings underscore the importance of long-term, local observations in understanding how the climate is changing across Illinois and beyond. Wallin hopes the work will help refine wind energy projections and encourage improvements in reanalysis data incorporating ground-based observations.

“I think it’s interesting for weather and wind power here, but it adds to a growing body of work talking about the accuracy of reanalysis data, and maybe growing research into improving reanalysis data, perhaps by including the weather station data in their reanalysis data,” she said. “Weather station data is all over the place; it’s tough to work with it on a large scale. I think many people just use the reanalysis data and accept it as accurate. It’s important to ground truth and ensure that it makes accurate predictions.”

The team hopes to expand the project beyond Illinois to see whether similar trends appear elsewhere in the world.

“We’re going to another project at a global scale,” Wallin said. “Using many of these techniques and expanding the work to a global scale and adding more data will be the next steps, to see if these trends hold globally and what that can mean for wind power, circulation, and weather.”